Thursday, August 31, 2006

More Work at Low Pay Increases Household Income

The Census Bureau released a report Tuesday with a positive spin, noting that income in most US households rose for the first time since 1999. Other data in the report shows that the rise in income results from taking on part-time jobs, not real increases in hourly wages.

"A rising tide lifts all boats," lost all meaning some time ago. Of course, the economy is not an ocean tide, an information system, a price structure nor anything other than a socially constructed system of agreements on the production and distribution of the material goods of life. All such systems evolve to increase the benefit of the rule makers to the detriment of everyone else; which evolution seems to be accelerating in our country over the last few years.

We can take little comfort from the increase in real income detailed by the Census Bureau report. Instead, the brazen attempt to put lipstick on this pig fills me with revulsion. Bad enough that the children of the poor often live in environments hostile to healthy families; now we see the parents of poor children forced to take on second jobs just to survive.

Coupled with the large increase in the uninsured population, the total picture is one of increasing social inequality.

"A rising tide lifts all boats," lost all meaning some time ago. Of course, the economy is not an ocean tide, an information system, a price structure nor anything other than a socially constructed system of agreements on the production and distribution of the material goods of life. All such systems evolve to increase the benefit of the rule makers to the detriment of everyone else; which evolution seems to be accelerating in our country over the last few years.

We can take little comfort from the increase in real income detailed by the Census Bureau report. Instead, the brazen attempt to put lipstick on this pig fills me with revulsion. Bad enough that the children of the poor often live in environments hostile to healthy families; now we see the parents of poor children forced to take on second jobs just to survive.

Coupled with the large increase in the uninsured population, the total picture is one of increasing social inequality.

Rumsfeld & Rhetorical Errors

The Washington Post yesterday said "Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld warned yesterday that "moral and intellectual confusion" over the Iraq war and the broader anti-terrorism effort could sap American willpower and divide the country, and he urged renewed resolve to confront extremists waging "a new type of fascism."

The ancient rhetorical tactic of attacking one's opposition in lieu of their arguments was identified centuries ago and given a Latin name, ad hominem. Beginning students of rhetoric and logic learn to recognize this fallacy in first-year classes.

Rumsfeld is further quoted as saying, "Any kind of moral and intellectual confusion about who and what is right or wrong can severely weaken the ability of free societies to persevere." So, his argument appears to mean that free and open debate will lead to our conquest by the enemies of free and open debate, thus ending free and open debate.

I guess we can no longer blog for fear of bringing down Western civilization.

Asked to name the morally and intellectually confused enemies of free and open debate, Rumsfeld flamed out, unable to come up with even a single example.

Well, Mr. Secretary, I humbly submit that you should spend some quality time in front of a mirror.

The ancient rhetorical tactic of attacking one's opposition in lieu of their arguments was identified centuries ago and given a Latin name, ad hominem. Beginning students of rhetoric and logic learn to recognize this fallacy in first-year classes.

Rumsfeld is further quoted as saying, "Any kind of moral and intellectual confusion about who and what is right or wrong can severely weaken the ability of free societies to persevere." So, his argument appears to mean that free and open debate will lead to our conquest by the enemies of free and open debate, thus ending free and open debate.

I guess we can no longer blog for fear of bringing down Western civilization.

Asked to name the morally and intellectually confused enemies of free and open debate, Rumsfeld flamed out, unable to come up with even a single example.

Well, Mr. Secretary, I humbly submit that you should spend some quality time in front of a mirror.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Of Gutters and Murder

His father was murdered.

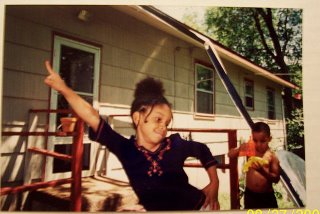

C.J.,the little boy in this picture, plays with water pistols while his sister strikes a pose. His father just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. The family tells me he never hurt anyone, he was a harmless man tied up in nasty business.

C.J.'s mom works for the postal service.

I borrowed the photo from the grandmother of the kids, a woman I work closely with. Connie is blessed with a sharp mind and a kind heart. I often seek her help with puzzling questions of the application of law and regulations. She is white; her former husband was black; by the illogic of race relations, that makes the grandchildren black.

Whenever I would visit Connie in her cubicle, this photograph would catch my eye. Something about it disturbed me deeply.

It was not Imani, looking pretty and happy in the yard. And God help me, the fact that C.J.'s father was murdered didn't really hit me emotionally. I regret the man's fate in a sort of general, abstract way. Like something that happened in a foreign country, far, far away.

Incidentally, the family lives in Kansas City, Mo. Last year, that city experienced 120 homicides. Adjoining Johnson County, Kan., with roughly the same population, had a total of 10 murders in 2005. Of course, in Kansas City, virtually all the victims were black.

No, the gutter torn from the back of the house bothered me. You can see it hanging off the house in the picture, right behind C.J.'s head. The angle artfully echos Imani's pose.

In the last few years I've put gutters on three houses. The new, plastic materials make the job relatively easy, well within the reach of even a rank amatuer like myself.

I have no reason to think that C.J.'s father would have fixed the gutter, and no reason to think he would not. Connie told me that, before the murder, he had started to do things around the house. I knew after the murder, no one would fix it any time soon.

Connie told me about water problems at the house where her grandkids lived. I told her if she would pay for materials, I'd fix the gutters for free.

So, on a warm day a few years ago, I headed off to the builder's supply store and bought all the materials I'd need. I lashed them to the roof of my ancient Aerostar minivan, along with my 32' and 16' ladders, and off I went.

Once at the house, I unloaded the gutters, downspouts, nails and other stuff. I set the long ladder up at the corner of the house. The angle was less than ideal, and the ladder's feet sat on very damp soil. But I charged right up anyway, eager to get to work.

A moment after I reached the top, the ladder slid down and I landed on top of it. Stunned, I paused for a moment. My chin bled profusely and my shin hurt like the devil. After a moment, I picked myself up and went inside.

Connie gave me bandaids and tylenol. I waited to see if the bleeding would stop, but it didn't. I wanted to finish what I had come to do, but I started feeling weak and lightheaded. I decided to go home.

I drove slowly, across the state line, a drive of about 40 minutes on I-435. I left an area of smaller homes and somewhat unkept yards and arrived in my neighborhood of big houses on immaculately groomed lots. From one-car garages and torn gutters to three car garages and lawn services.

The rest of my family was at church for some social activity. I showered and put on fresh clothes and band aids, then I joined them.

As I was eating my pizza, my wife came and found me. "Someone told me you were here, and you are bleeding."

"I am?" I asked.

"Don't you think you should go see the doctor?"

"Oh, I guess so."

So I called the doctor and they sent me to the ER. I got 12 stitches in my chin and 13 in my shin. I went home and parked myself in front of the tv.

A few weeks later I called Tony, a pal at work. He agreed to help me fix the gutters, so long as he did not have to climb the ladders.

We met over at the house on a week-end morning and went to work. Tony held the ladder and watched what I was doing. He helped me think through the work and kept me from making some mistakes. After working most of the afternoon, we were done. About five hours of work.

The black spot on my shin is long gone, but I still have a little scar on my chin to remind me not to take on too big a project on my own.

And now, when I look at the picture of Imani and C.J., the hanging gutter does not bother me.

Sunday, August 13, 2006

In Memory of Abigail: June 20 - July 7, 2006

The infant cradled in my arms would never know love. She could not cry; could not suffer pain or hunger; could not see or hear.

Two weeks earlier, almost two months ago now, Abigail entered the world with no heartbeat. She did not breathe. Doctors labored heroically to revive her, to no avail. The death certificate was signed.

Then someone noticed her trying to breathe.

Jane and I, not knowing, were on our way to work. Our friend Sunny called "What are you doing?" she asked.

"Going to work," Jane said.

"Pray for my baby."

We headed immediately over to the hospital. Sunny lay in the maternity ER, suffering. The baby's father, J.P., stood close by her side. Family and friends surrounded her.

After some time, the staff wheeled in an incubator on a small cart. Little Abigail, pale and beautiful and still, appeared. She was to be whisked off to Children's Mercy hospital, where she would receive the highest level of care. But she paused in her journey long enough for her mother to touch her. Then Abigail and her attendants left.

Premature separation of the placenta from the wall of the uterus occurs in about one in every 120 pregnancies. In many cases, the baby remains unharmed by a partial separation; even with only half of the placenta working; a sufficient supply of oxygen still passes from the mother to the baby. In Abigail's case, most or the entire placenta tore off the uterine wall without warning, suddenly ripping away for no apparent reason. Starved of oxygen, her brain cells began to fail.

When I visited Abigail a few days later, in the neo-natal intensive care unit, I found the signs of encouragement I wanted to see. She appeared to respond to the sound of my voice. Her tiny hand clasped mine with a firm grip. Despite the disturbing way her eyes rolled around, I took away hope she would improve.

But tests performed a few days after birth confirmed our worst fears. Abigail's brain showed virtually no signs of normal function. The doctors said she would have constant seizures and gave her medicines to mitigate the electrical storms raging in her skull.

Sunny, J.P. and Pastor Jan from St. Paul's arranged for Abigail's baptism into Christianity to be performed at the hospital. And, the Sunday after she was born, in a large room that looked like an OR, surrounded by the love of family and friends, Abigail was baptized.

The following Sunday, she went home with her mother.

Abigail turned two weeks old on the Fourth of July. Family and friends gathered in her mother's home to wish her well. We took turns holding her. As I looked on the perfect, sleeping infant in my arms, I found it difficult to think about her spirit. Though I knew that, with no brain function there would be no mind, I found it hard to believe she was anything less than a whole, perfect human being. Though my own mind told me I held an empty shell, my heart refused to accept it.

No, if her soul had ever been present, it had left before I ever got a chance to hold her.

As human beings, we often confuse wishful thinking with hope. We grab hold of the slightest flimsy excuses to justify our heart's desire, and run with them, telling ourselves our wishes will come true.

We easily fall into the traps of cliche and empty headed repetitions of piety when faced with immediate, personal tragedy. We say "Everything happens for a purpose," and then proceed to construct our own reasons why the conclusion came as it did.

I know Abigail strengthened the bond between her parents. She did the same for Jane and me, and perhaps other friends and family. She reminded me of my own blessings, chief among which are my daughters.

But if that was Abigail's true purpose, the price was too high. The loss outweighed the gain. I can only imagine some of the pain her mother and father feel; at some point, imagination recoils and will go no further.

Here we see the defects of cliched piety. The pain of this suffering cannot be justified by anything we understand. And exactly what do we understand?

I turn to the understanding in the book of Job. I find myself thinking about it a lot. Job, though a righteous man, suffers mightily. He complains to his friends at length, and finally, to God. His complaints are well founded. But God does not justify His actions. He responds to Job in some of the most poetic language of the Bible: "Where were you when I laid the earth's foundation? Tell me, if you understand." (Job 38:4)

Well, this answer is no answer. It explains nothing. God is God and we are not. God understands what He understands, and we do not. God does not justify Himself to us.

Even with limited human understanding, we can replace wishful thinking with genuine hope. We can face the real world, as it actually is, with clear eyes, and a calm and steady gaze. Sunny and J.P. endure, and in the midst of tragedy, they make plans for the future.

Abigail died at home Friday, July 7th.

On a very stormy Tuesday evening, July 11th, over eighty, perhaps over a hundred people came to visit Abigail and her family. As we drove to the funeral home, a rainbow struggled to appear in the East.

Led by Pastor Jan, we prayed together, commending the spirit of the infant to God.

Abigail lay by herself in a small room, away from the crowd of friends and family gathered in the larger room nearby. She looked pale and peaceful. She wore a white crotched cap and dress; beads around her neck strung together just for her; a grandfather's rosary at her feet. Ever so gently, I touched her tiny hand. Then we left.

As we drove away, rainbows stretched across the sky, under torn curtains of black and gray clouds. The rainbows reminded all of us of God's promises of renewal and hope. I, for one, could think about little else.

Every normal human being shares a heritage with his or her fellows. We occupy the time between birth and death with hopeful activities, striving to fully realize the promises within each of us. Our maker built us just so, giving us certain needs. We observe the same details of our nature whether or not we credit God, evolution or God-guided evolution with our design.

We never exist alone. We live in community. This is how we are made.

Our communities lift us up; they sustain us. Our families and friends share our joys thereby multiplying them. When we share our grief, it divides.

I also believe we find the greatest happiness and serenity when we embrace faith in God. When we choose to trust God, we find courage to endure the suffering that life inflicts on us. We do more than merely endure; we rise up out of the ashes with hope. This is how we are made.

Fluffy white clouds drifted in blue Midwest skies on the day of the funeral; the air purified by the rampaging thunderstorms of the night before. The tiny pastel casket came to rest on a grassy hill; bells rang in the distance.

Towards the end of the service, individuals took one of several dozen balloons and walked to an open space. As they handed out the balloons, a single green one escaped. It climbed quickly out of sight. A minute later, three dozen or so pink, green, white and yellow balloons took off together.

I could not help but think about April 19, 2005. Then, with a mere handful of friends, I released a balloon into the air in memory of children taken too soon. This time, I just watched.

The human condition requires us to know grief. Sooner or later, each and every one of us faces irrevocable loss. But our endowment includes the capacity to choose our response to grief. We can allow ourselves to fully experience it, and then to move on. Or we can make a vain attempt to avoid it. This is how we are made.

The weight of our burdens lightens when we choose to share them with God. This is how we are made.

Many people choose not to believe in God, choose to deny Him and therefore cannot trust in Him. They require external proof, as if it makes sense to require proof of the transcendent. By their understanding, that is the wiser path. But what a lonely, empty path; everything reduced to matter and matter in motion. Is this how we are made?

The choice, really, is one of choosing how to live. One can seek to live only by philosophically, logically justified beliefs, or not. To me, the choice is between an ultimately sterile, barren, meaningless existence; or a life worth living.

Whatever other purposes the life of Abigail served, she challenged us to hold on to our faith. She teaches us about hope, and about God. She shows us the way. This is how we are made.